| disease | Fistula Disease, Chest Fistula |

| alias | Pectus Excavatum |

Fistula disease, also known as pectus excavatum, is a congenital and often familial condition. It is more common in males than in females, with a reported male-to-female ratio of 4:1, and is inherited as a sex-linked dominant trait.

bubble_chart Etiology

Most people believe that pectus excavatum, or funnel chest, is a deformity caused by the overdevelopment of the costal cartilage and ribs in the lower chest, leading to a compensatory backward displacement of the sternum.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

Fistula disease pectus excavatum is a deformity where the sternum, costal cartilage, and part of the ribs sink inward toward the spine, forming a funnel-like shape. In most cases of fistula disease pectus excavatum, the sternum begins to curve backward at the level of the second or third costal cartilage, reaching its lowest point slightly above the xiphoid process, then curves forward to form a boat-like deformity. The sides or outer edges curve inward, forming the side walls of the fistula disease pectus excavatum. The ribs in fistula disease pectus excavatum have a steeper slope than normal, curving sharply from the posterior superior to the anterior inferior, reducing the front-to-back distance. In severe cases, the deepest part of the sternal depression can reach the spine. In younger patients with fistula disease pectus excavatum, the deformity is often symmetrical. However, as they age, the deformity becomes increasingly asymmetrical, with the sternum often rotating to the right. The depression of the right costal cartilage is usually deeper than the left, and the right breast development is poorer than the left. The back often appears flat or rounded, and scoliosis gradually worsens with age. Scoliosis is less noticeable in younger patients but becomes more pronounced after puberty. The fistula disease pectus excavatum deformity compresses the heart and lungs, often displacing the heart to the left thoracic cavity. Children often exhibit a characteristic weak posture: a forward-protruding neck, rounded and sloping shoulders, and a pot-bellied abdomen.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsFistula disease pectus excavatum is commonly seen in children under the age of 15 and is rarely observed in patients over 40 years old. This may be because pectus excavatum and scoliosis associated with fistula disease compress the heart and lungs, impairing respiratory and circulatory functions, leading to a shortened lifespan, with patients often passing away before the age of 40.

Mild cases of fistula disease pectus excavatum may be asymptomatic, while more severe deformities can compress the heart and lungs, affecting respiratory and circulatory functions, reducing lung capacity, increasing functional residual capacity, and decreasing exercise tolerance. Young children often experience recurrent respiratory infections, presenting with cough and fever, and are frequently diagnosed with bronchitis or bronchial asthma. Circulatory symptoms are less common in young children, but older children may experience dyspnea after activity, rapid pulse, palpitation, and even precordial pain, primarily due to cardiac compression, inadequate cardiac output during exercise, myocardial hypoxia, and consequent pain. Some patients may also exhibit arrhythmias and systolic murmurs.

Fistula disease pectus excavatum is sometimes associated with pulmonary hypoplasia, Marfan syndrome, asthma, and other conditions. When these diseases coexist, they often result in intolerable deformities for the patient, necessitating early surgical correction.

Fistula disease pectus excavatum is very easy to diagnose clinically, with the deformity being obvious at a glance. However, determining the severity of fistula disease pectus excavatum is relatively difficult, and there are many descriptive methods currently used in clinical practice.

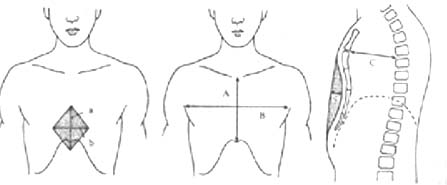

1. Surface ripple zoning map is an objective method to describe the deformity. It uses the projection method of light source and grid to photograph the ripple contour image of the depressed part of the chest wall. Based on the interval and number of ripple contours, the data is input into a computer via a digital converter to calculate the volume of the depressed part, determine the severity of the fistula disease pectus deformity, and evaluate the effect of surgical treatment.2. Fistula disease pectus index (FI) is another method to express the deformity (Figure 1).

| FI | = | a×b×c |

| A×B×C |

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of fistula disease pectus index and its measurement method

a. Longitudinal diameter of the depressed part of fistula disease pectus excavatum; b. Transverse diameter of the depressed part; c. Depth of the depressed part;

A. Length of the sternum; B. Transverse diameter of the thorax; C. Shortest distance from the sternal angle to the vertebral body

The criteria for judging the degree of depression in fistula disease pectus excavatum are:

grade III: FI>0.3, grade II 0.3>FI>0.2, grade I: FI<0.2

3. Water injection measurement in the fistula disease pectus area. The patient is placed in a supine position, water is injected into the fistula disease pectus area, and then the amount of water is measured to understand the severity of fistula disease pectus excavatum. The water capacity in severe cases can reach about 200ml. Some people use plasticine to fill the fistula disease pectus area, shape it, and then immerse it in water to easily measure the volume of the depressed part.

X-ray examination can show the posterior part of the ribs being straight, the anterior part sharply inclined downward, the heart shadow often shifted to the left thoracic cavity, with a distinct radiolucent area in the middle of the heart shadow (Figure 2). The right heart border often overlaps with the spine, and in severe cases, the heart shadow may be completely located in the left thoracic cavity. Older patients often have scoliosis. Lateral chest X-rays can show the sternum significantly curved backward, with the lower end of the sternum sometimes reaching the anterior edge of the spine.

Figure 2 X-ray examination of fistula disease pectus excavatum

Posteroanterior view: Radiolucent area in the heart shadow of fistula disease pectus excavatum

Chest CT scans can more clearly show the severity of thoracic deformity and the degree of cardiac compression and displacement.

Electrocardiogram may show inverted or biphasic P waves in V1, and there may also be right bundle branch block. Cardiac catheterization can record diastolic slopes and plateaus, similar to those seen in constrictive pericarditis. Heart blood vessel angiography shows right heart compression deformity and obstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

(1) Surgical Indications

Fistula disease pectus excavatum affecting cardiopulmonary function and causing psychological burden should be treated surgically. Fistula disease pectus with an index greater than 0.2 should also be treated surgically. The timing of surgery is still debated, with most experts recommending surgery between the ages of 3 to 10. Some advocate for immediate surgery upon noticing significant deformity, regardless of age, rather than waiting for severe clinical symptoms to develop. The younger the patient, the better the treatment outcome and the smaller the surgical scope required. Infants and young children rarely require blood transfusions during surgery and seldom need resection beyond the costal cartilage joints. Older patients often require resection of bony ribs and may need blood transfusions. In fact, some symptoms may not be noticed before surgery but disappear postoperatively. In infants and young children, the chest wall shows significant paradoxical inward movement during inspiration, exacerbating the deformity. Therefore, some authors believe that if the deformity persists during forceful expiration, it should be considered a constant deformity and corrected surgically.

(2) Surgical Methods

1. Rib Osteotomy: For unilateral, deep pectus excavatum not involving the sternum, rib osteotomy can be performed. The method involves making a curved incision from the midline to the affected side, dissecting the deformed costal cartilage and ribs under the perichondrium and periosteum, making multiple transverse incisions to correct the deformity, pulling the costal cartilage upward toward the sternum, suturing the costal cartilage to the front of the sternum, and then suturing the skin. This simple surgery is suitable for milder cases of pectus excavatum.

2. Sternum Elevation: This involves resecting the entire length of the deformed costal cartilage (3rd to 6th ribs) under the perichondrium to completely free the sternum below the 2nd rib. A transverse osteotomy is made at the level of the 2nd rib on the posterior sternal plate, and a costal cartilage graft is inserted and fixed at the osteotomy site, elevating the sternum. The 2nd costal cartilage is then obliquely cut from anterior to posterior, and the medial end is overlapped and sutured to the lateral end, using a three-point fixation method. Finally, the intercostal muscles and rectus abdominis are sutured to the sternum, and the skin is closed. This method may result in paradoxical breathing postoperatively, which can be prevented by using metal pins or plates for reinforcement. The downside is the need for a second surgery to remove the metal fixation, making it less popular.

3. Sternocostal Elevation: Particularly suitable for younger patients with flexible costal cartilage and ribs. After a midline skin incision, the depressed sternum and costal cartilage are exposed. The ribs are freed under the perichondrium, and the 3rd to 7th costal cartilages are cut near the sternum. The intercostal muscles are incised laterally to fully mobilize the ribs and costal cartilage. Multiple transverse wedge resections are made on the ventral side of the costal cartilage to elevate it back to its normal position. Excess cartilage is trimmed, and the corresponding ends are sutured with polyester sutures to increase the anteroposterior diameter of the thorax to near normal. The combined upward pull of the costal cartilages on both sides elevates the depressed sternum, hence the name sternocostal elevation.

4. Sternal turnover with upper and lower vascular pedicle. A midline skin incision is made on the chest and abdomen, and the pectoralis major muscles on both sides are dissected laterally to expose the depressed sternum and the deformed ribs and costal cartilages on both sides. The rectus abdominis muscle is dissected along its lateral edge to the level of the umbilicus. The lower edge of the costal arch is incised, and the sternum and the inner surface of the costal cartilages on both sides are dissected with fingers until the lateral side of the depressed deformity is reached. The 7th to 3rd costal cartilages and intercostal muscles are severed from their origins on both sides of the deformed costal cartilages. The internal thoracic arteries and veins are isolated at the level of the 2nd intercostal space and dissected 4-5 cm upwards and downwards. The sternum is transversely cut at this level using a wire saw, completely freeing the depressed sternum and the costal cartilages on both sides. The sternal plate and costal cartilages, along with the internal thoracic arteries and veins and the rectus abdominis muscle, are then crossed in a cruciform manner. The most depressed part of the sternum becomes the most prominent part after turnover, and it can be appropriately trimmed to make the sternum flat. The transverse sternal ends are sutured with stainless steel wires, and the corresponding costal cartilage ends and intercostal muscles are sutured with polyester sutures. Excessively long costal cartilages are excised during suturing to ensure that the turned-over sternocostal plate fits perfectly in its original position. After fixation, a closed drainage tube is placed behind the sternum, and the pectoralis major muscles, subcutaneous tissues, and skin are sutured.

In this procedure, the internal thoracic arteries and veins and the rectus abdominis muscle are not severed, ensuring normal blood circulation in the sternum and promoting normal growth and development post-surgery. As long as the internal thoracic arteries and veins are sufficiently mobilized to a length of 4-5 cm during the operation, flipping the sternum usually does not encounter any difficulties. Although the internal thoracic arteries and veins and the rectus abdominis muscle cross in a crisscross pattern, the stirred pulse is strong, and venous stasis does not occur. Postoperatively, the chest wall is stable without paradoxical breathing, allowing patients to ambulate early. The correction of the deformity is satisfactory. In some cases, a grade I localized depression may appear at the transverse sternal incision in the upper chest 2-3 months postoperatively. Some advocate the use of a sternal bone traction frame to correct this defect.

5. Sternal Turnover with Rectus Abdominis Muscle Pedicle This method differs from the sternal turnover with upper and lower vascular pedicles in that it involves cutting the internal thoracic arteries and veins, retaining only the rectus abdominis muscle pedicle as the source of blood supply. The surgical procedure is essentially the same as the previous method, except that the internal thoracic arteries and veins are ligated and severed before transecting the sternum. The sternum and costal cartilage plate are then flipped 180° with the rectus abdominis muscle pedicle, and the deformed sternal plate is trimmed and sutured back into its original position.

6. Pedicle-Free Sternal Turnover (Wada Method) A midline sternal or bilateral submammary transverse incision is made. The pectoralis major and rectus abdominis muscles are mobilized to expose the deformed sternum, costal cartilages, and ribs. Starting slightly lateral to the beginning of the deformity, the costal cartilages are sequentially incised from the costal arch upwards, and the costal cartilages are severed. The costal cartilages and pectoral muscles are then stripped from the periosteum. The sternum is transected at the intercostal space above the downward depression. Any attached intercostal muscles and soft tissues are completely removed and washed with antibiotic solution. The sternal plate, flipped 180°, is fixed with wires at the manubrium. Excessively long costal cartilages are trimmed and sutured with polyester sutures to the corresponding ribs, followed by muscle and skin closure.

7. Sternal Turnover with Overlapping In some patients with a flat or depressed upper chest, the upper end of the sternal plate can be cut into a beveled shape after flipping and inserted into the periosteum in front of the manubrium, allowing partial overlapping of the pectoral muscles. The sternal plate is shifted upwards and fixed with wires. The overlapping sternum is sutured, and excessively long costal cartilages are also overlapped and sutured with polyester sutures, resulting in a more satisfactory correction of the chest wall contour postoperatively.

Sternal turnover is more suitable for adult patients, as other methods like sternal elevation are often inadequate for correction. Postoperative sternal turnover has not shown any issues with sternal blood supply, nor has it led to sternal destruction or rejection by the body. The surgical outcomes are satisfactory.