| disease | Bladder Neck Contracture |

Bladder neck contracture is another important issue of bladder neck obstruction. The so-called bladder neck refers to a tubular structure extending from the internal urethral orifice into the urethra for about 1 to 2 centimeters in length. It includes the internal sphincter, but the internal sphincter is not the entirety of the bladder neck. In terms of etiology, bladder neck contracture can be classified as congenital or acquired. Congenital cases often have no other clear causes besides typical local pathological changes and are more common in males. Acquired cases, on the other hand, are often caused by local chronic inflammations such as posterior urethritis, prostatitis, or trigonitis, with females being affected at rates not lower than males. While congenital cases are more commonly seen in children, often presenting with symptoms of urinary obstruction before the age of six, it is not rare for cases to manifest in individuals aged 20 or 30 and older.

bubble_chart Pathological Changes

The typical pathological change is a slight protrusion of the urethral orifice into the bladder, particularly noticeable on the posterior lip. The local tissue is thickened and firm, with no actual narrowing of the posterior urethra. However, when examined with instruments or during surgery by finger palpation, the posterior urethra often feels tight and difficult to dilate. In some cases, this hypertrophic tissue change may extend to the bladder trigone, causing a prominent bulge in the bladder. Microscopic examination reveals three possible conditions: first, hyperplasia of muscle tissue; second, hyperplasia of connective tissue; and third, hyperplasia of glandular tissue (Leadbetter 1959). In cases where muscle tissue hyperplasia predominates, the obstruction may result not only from the mechanical effect of local tissue thickening but also from neuromuscular dysfunction, known as achalasia. In acquired cases, apart from a history of recurrent inflammation, there is significant inflammatory infiltration within the aforementioned hypertrophic tissue.

bubble_chart Clinical ManifestationsDifficulty urinating, straining to urinate, interrupted urination, children crying during urination, dribbling urine, and sometimes paradoxical urination. When combined with a urinary tract infection, these symptoms become more pronounced. During physical examination, a distended bladder in the lower abdomen may be detected, though it is not always obvious.

The diagnosis of this disease primarily relies on the history of dysuria as the main clue. Therefore, detailed information about the urinary obstruction should be obtained. During physical examination, attention should be paid to whether there are masses in the bilateral renal regions, and palpation and percussion should be performed to check for bladder distension. However, the definitive diagnosis of this disease depends on cystourethroscopy and X-ray examination.

1. Cystoscopy: It is best to use a cystourethroscope or a universal cystoscope, which can examine both the bladder and the urethra. Through this examination, it can be observed that the posterior urethra is very tight when the cystoscope is inserted, but it can still be advanced. During the examination, the posterior edge of the urethral orifice may appear slightly raised, the trigone area may also be more prominent, and multiple trabeculations and diverticula can be seen. The ureteral orifices are often visible. This examination can exclude other bladder and urethral pathologies, such as bladder diverticula, hypertrophy of the interureteric ridge, bladder submucosal nodules, urethral strictures, posterior urethral valves, and hypertrophy of the verumontanum.

2. X-ray examination: A plain film can exclude radiopaque urinary calculi. Intravenous pyelography is particularly important as it provides an overview of the bilateral renal function. Due to the long-term lower urinary tract obstruction, especially in congenital cases, the upper urinary tract is often significantly dilated, with the ureters potentially as thick as the intestines. A cystogram taken after releasing the abdominal pressure band may show slight protrusion of the bladder neck into the bladder, which is highly significant for diagnosis. Lower urinary tract obstruction caused by posterior urethral strictures or valves often does not present this change; instead, the urethral orifice may appear funnel-shaped, which can help differentiate it from this disease.

3. Measurement of residual urine: This is also important for diagnosing this disease, though it may sometimes be unreliable. The following should be noted: Although the patient may not empty the bladder completely in one voiding, resting for 2–3 minutes after voiding may allow the passage of a significant amount of urine. If residual urine is measured after several such voidings, the residual volume may be minimal. Additionally, if the upper urinary tract is markedly dilated and vesicoureteral reflux is severe, the measured residual urine may include urine from the upper tract, which is essentially pseudo-residual urine. These factors must be considered when performing this test.In summary, the diagnosis of this disease is primarily based on a long history of dysuria. Through endoscopic and X-ray examinations, and by excluding other obstructive pathologies, the characteristic features of this disease—such as tightness of the posterior urethra during instrumentation and slight protrusion of the bladder neck into the bladder on cystography—can confirm the diagnosis.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

To relieve this type of bladder neck obstruction, the following methods can be used:

1. **Urethral dilation**: For early-stage patients with minimal residual urine, no infection, and good renal function, urethral dilation can be employed.

2. **Transurethral resection of hypertrophic bladder neck tissue**: Currently, electrocautery is commonly used, similar to transurethral resection of hypertrophic prostate tissue. In children, removing 5–8 pieces of tissue suffices, whereas adults require more extensive resection. Specialized instruments are necessary for this procedure.

3. **Surgical treatment**: There are two approaches:(1) **Incision of the bladder**: The bladder is opened to examine the bladder neck. If the tissue is hypertrophic and inelastic, with a tightly closed urethral orifice that can barely admit a fingertip, and sometimes a posterior lip protruding into the bladder, the posterior lip is incised to expose the mucous membrane. A wedge-shaped excision of the submucosal tissue is performed, followed by suturing of the mucous membrane. A Foley catheter is left in place for traction and hemostasis, while also maintaining dilation of the bladder neck. The advantage of this procedure is that it not only relieves bladder neck obstruction but also allows further assessment of the bladder's internal condition.

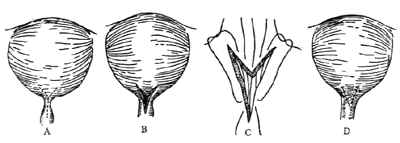

(2) **Suprapubic exposure of the bladder**: The bladder is exposed suprapubically without incision, and the bladder neck is exposed retropubically. A Y-shaped incision is made at the anterior aspect, followed by V-shaped suturing to enlarge the bladder neck (Figure 1). This method is highly effective for enlarging the bladder neck but has the drawback of not allowing simultaneous exploration of the bladder's interior.

**Figure 1: Bladder Neck Y-V Plasty**

A. Y-shaped incision B. Narrowing enlarged C. V-shaped suturing D. Completion of suturing

Posterior urethritis; prostatitis; trigonitis