| disease | Fecal Fistula |

| alias | Fecal Fistula |

A fecal fistula refers to an abnormal passage formed between the reproductive organs and the intestines. The most common type in gynecological and obstetric practice is a rectovaginal fistula. Fecal fistulas caused by prolonged labor may sometimes be complicated by urinary fistulas. Additionally, small intestine or colovaginal fistulas can also occur. Reproductive organ fistulas are an extremely distressing and painful condition. Due to the inability to control urine and feces, the vulva is constantly soaked in urine, causing not only physical suffering but also significant psychological distress as patients fear social interaction and are unable to participate in productive labor. Strengthening maternal healthcare, promoting modern delivery methods, proper management of childbirth, and improving surgical quality can help avoid injuries to reproductive organs, thereby significantly reducing the incidence of reproductive organ fistulas.

bubble_chart Etiology

The causes of fecal fistula are essentially the same as those of urinary fistula. Additionally, many cases result from failed suturing of perineal grade III lacerations or from sutures penetrating the intestinal mucosa during episiotomy repair. Although small intestine and colonic vaginal fistulas are relatively rare, they are mostly caused by surgical injuries or postoperative adhesions.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

If the fistula is large and close to the vaginal opening, both formed and semi-formed stools may pass through the vagina, accompanied by uncontrollable flatulence. These symptoms worsen when the stool is loose. If the fistula is small and the stool is dry, there may be no fecal discharge from the vagina, except during episodes of loose stool when fecal leakage occurs, though flatulence remains uncontrollable. If a fecal fistula coexists with a urinary fistula, the urine often contains fecal matter or is accompanied by flatulence. The vagina and vulva may develop chronic vulvar dermatitis due to frequent irritation from feces and fecal-contaminated secretions.

bubble_chart DiagnosisThe symptoms of rectovaginal fistula are relatively straightforward, making diagnosis easier than urinary fistula. Large fistulas can be visualized under a vaginal speculum or palpated during digital examination. Smaller fistulas may be harder to detect, appearing only as a small, bright red granulation tissue on the posterior vaginal wall. If a uterine probe is inserted at this site while a finger is placed in the anus, the finger and probe meeting confirms the diagnosis. If a small intestine or colovaginal fistula is suspected, in addition to reviewing surgical history, a barium enema or barium meal fluoroscopy may be considered.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

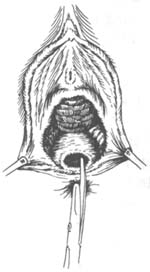

The treatment for fecal fistula is surgical repair. The repair outcome is better than that for urinary fistula. The chance of spontaneous healing after injury is also higher than that for urinary fistula. Fresh injuries (such as surgical or traumatic) should be repaired immediately. For old fecal fistulas, such as high-positioned rectovaginal fistulas, follow the principles, methods, and surgical requirements for urinary fistula repair. Separate the surrounding tissues of the fistula, detach the vaginal wall from the rectal mucosa, suture the rectal wall first (without penetrating the mucosa), and then suture the vaginal wall. If the rectovaginal wall is close to the anus, first cut the rectovaginal septum between the anus and the fistula along the midline to create a perineal grade III laceration, then proceed with the repair (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Before repairing a low-positioned rectovaginal fistula, the rectovaginal septum between the anus and the fistula is cut.

If both fecal and urinary fistulas coexist, they should be repaired simultaneously. If the fecal fistula is large or there is excessive scar tissue, making the surgery difficult, a colostomy on the abdominal wall and urinary fistula repair can be performed first. After the urinary fistula heals, wait for 4 weeks before repairing the fecal fistula. Once successful, restore the colostomy. Although this situation is rare, the methods and steps must be carefully considered based on specific circumstances.

For rectovaginal fistulas with a large fistula opening or excessive scar tissue (often caused by corrosive suppositories in the vagina), or if the fistula has failed multiple repair attempts and further repair is deemed unlikely to succeed, a permanent artificial anus surgery may be considered.Diagnosed small intestine or colovaginal fistulas should be repaired via abdominal surgery or undergo intestinal resection and anastomosis.

Preoperative preparation and postoperative care are crucial for the healing of fecal fistula repairs. Therefore, 3–5 days before surgery, start a low-residue semi-liquid diet and administer metronidazole 0.2g, 3–4 times daily for 3–4 days; gentamicin 80,000 units, intramuscularly, twice daily for 3–4 days; or neomycin 1g orally the day before surgery, or streptomycin 1g orally daily for 3–4 days to reduce the risk of intestinal infection. The day before surgery, take 15g of senna leaf (infused) or perform a thorough rectal and vaginal cleansing the night before. Postoperatively, continue the low-residue semi-liquid diet and control bowel movements for 3–5 days. Administer 5% opium tincture 5ml three times daily; continue metronidazole to prevent infection and promote wound healing. Starting from the fourth postoperative day, take 30–40ml of liquid paraffin nightly or 15g of senna leaf daily to soften or thin the stool for easier passage (discontinue if bowel movements become too frequent). Additionally, maintain perineal hygiene postoperatively.

The prevention of fecal fistula is essentially the same as that of urinary fistula. Additionally, proper assistance during delivery should be provided to avoid grade III perineal lacerations. During episiotomy suturing, care must be taken to ensure sutures do not penetrate the rectal mucosa. Routine rectal examination should be performed after perineal suturing, and any sutures found in the rectal mucosa should be promptly removed. For abdominal surgeries involving extensive pelvic floor dissection where the sigmoid colon must be used for coverage, care should also be taken not to penetrate the intestinal wall when suturing the pelvic peritoneum. When suturing the pelvic peritoneum, avoid exposing rough surfaces to prevent intestinal adhesion, infection, necrosis, and the formation of vaginal fistulas.