| disease | Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome |

| alias | Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome, Systolic Click-murmur Syndrome |

Mitral valve prolapse syndrome refers to a series of clinical manifestations caused by various factors that lead to the mitral valve leaflets prolapsing into the left atrium during heart contraction, resulting in mitral valve insufficiency. It was previously known as systolic click-murmur syndrome, Barlow syndrome, floppy valve syndrome, and others.

bubble_chart Etiology

Primary mitral valve prolapse syndrome is a congenital connective tissue disorder, and its exact {|###|}disease cause{|###|} remains unclear. It can occur in all age groups, but is more common in females, particularly those aged 14 to 30. One-third of patients have no other organic heart disease and present solely with mitral valve prolapse as the clinical manifestation. It can also be observed in patients with Marfan syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, nodular {|###|}stirred pulse{|###|} arteritis, among others, with posterior leaflet prolapse being more frequent. In some cases, the {|###|}philtrum{|###|} is attributed to hereditary collagen tissue abnormalities, which under electron microscopy show reduced and fragmented type III collagen fiber production, progressive degeneration of collagen fibers in the connective tissue center, and fibrin deposition; elastic fibers exhibit fragmentation and dissolution. The pathological hallmark of mitral valve prolapse is myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve, with spongy layer hyperplasia invading the fibrous layer, significant thickening of the spongy layer accompanied by proteoglycan accumulation, localized thickening of the atrial surface of the valve leaflet, and fibrin and platelet deposition on the surface. The prolapsed mitral valve leaflet bulges between the chordae tendineae, forming a hemispherical protrusion toward the left atrium, with the leaflet becoming elongated and enlarged in area. In severe cases, the mitral annulus dilates. Concurrently, the chordae tendineae become thinner, longer, twisted, and subsequently fibrotic and thickened. Chordal abnormalities are most pronounced where the leaflet is most affected. Due to these abnormalities, the mitral valve experiences uneven stress, leading to leaflet stretching and mucoid degeneration of the detached tissue; increased chordal tension may result in chordal rupture. The papillary muscles and adjacent myocardium may suffer from ischemia and fibrosis due to excessive traction and friction. Annular dilation and calcification further exacerbate the degree of prolapse.

Some cases of mitral valve prolapse may occur secondary to inflammation following {|###|}wind-dampness{|###|} or viral infections, with anterior leaflet prolapse being more common. Additionally, it can also be seen in patients with coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, and hyperthyroidism, who often exhibit concurrent mitral valve prolapse.Under normal circumstances, when the ventricles contract, the papillary muscles immediately contract as well. With the traction of the chordae tendineae, the mitral valve leaflets come close to each other. As the left ventricle continues to contract, the intraventricular pressure rises, causing the valve leaflets to bulge into the left atrium. The papillary muscles contract in coordination, tightening the chordae tendineae to prevent the valve leaflets from prolapsing into the left atrium, ensuring the leaflets remain tightly closed and the valve orifice shuts. At this point, the valve leaflets do not extend beyond the level of the valve annulus. When the mitral valve leaflets, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles, or valve annulus become diseased, the slackened valve leaflets may prolapse further into the left atrium after the valve orifice closes, leading to mitral regurgitation. Mitral valve prolapse can also be associated with abnormal left ventricular systolic function, such as segmental contraction, which leaves the chordae tendineae and valve leaflets in a slackened state during closure. This can cause or exacerbate their elongation, leading to prolapse in the advanced stages of mitral valve contraction. Mitral valve prolapse results in mitral regurgitation during left ventricular systole, increasing the workload on the left atrium and the diastolic load on the left ventricle.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations(1) Symptoms Most patients have no obvious symptoms, and when symptoms do occur, they are intermittent, recurrent, and transient. Common symptoms include:

1. Chest pain Occurring in 60-70% of cases, located in the precordial region, it may present as dull, sharp, or knife-like pain, usually mild in severity, lasting from minutes to hours, unrelated to exertion or emotional factors, and not relieved by nitroglycerin.

2. Palpitation Present in 50% of patients, the cause is unknown. It may be related to arrhythmias such as frequent ventricular premature beats, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, or ventricular tachycardia. However, Holter monitoring and His bundle electrogram studies have found that in some patients, the correlation between palpitation and arrhythmias is not strong.

3. Dyspnea and fatigue 40% of patients complain of shortness of breath and lack of strength, often as initial symptoms. Some patients experience reduced exercise tolerance without evidence of heart failure. Severe mitral regurgitation may manifest as left ventricular dysfunction.

4. Other symptoms may include dizziness, syncope, vascular migraine, transient ischemic attacks, as well as neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, nervousness, irritability, fear, and hyperventilation.

(2) Signs

1. Cardiac auscultation A mid-to-late systolic non-ejection click may be heard at the apex or medial to it. This sound occurs more than 0.14 seconds after the first heart sound and is caused by sudden tightening of the chordae tendineae or abrupt halting of leaflet prolapse. Immediately following the click, a mid-to-late systolic blowing murmur may be heard, often crescendo in nature, and occasionally holosystolic, which may obscure the click. Sometimes, a high-pitched, loud, musical mid-to-late systolic murmur resembling whooping cough or honking may be heard at the apex. The earlier and longer the systolic murmur appears, the more severe the mitral regurgitation. Any physiological or pharmacological maneuver that reduces left ventricular afterload, decreases venous return, or enhances myocardial contractility—thereby reducing left ventricular end-diastolic volume (such as standing, Valsalva maneuver, tachycardia, or amyl nitrite inhalation)—will cause the systolic click and murmur to occur earlier. Conversely, any factor that increases left ventricular afterload, increases venous return, or reduces myocardial contractility—thereby increasing left ventricular end-diastolic volume (such as squatting, bradycardia, beta-blockers, or pressor agents)—will delay the systolic click and murmur.

2. Other signs The cardiac impulse may be bifid, with sudden retraction of the heart during mid-systole (second phase) coinciding with the click, abruptly halting the outward movement. Patients often have an asthenic body habitus and may exhibit a straight back, scoliosis, lordosis, pectus excavatum, or other skeletal abnormalities.bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

(1) X-ray Examination: Most patients show no significant abnormalities in cardiac shadow. In cases of severe mitral regurgitation, the left atrium and left ventricle are markedly enlarged. Abnormalities of the thoracic skeleton are the most common findings. Left ventriculography reveals mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation, with the posterior mitral leaflet protruding into the left atrium in a lip-like manner during systole in the right anterior oblique projection. Asymmetric left ventricular contraction is observed, with strong contraction of the posterior basal or mid-ventricle, resulting in an inward "ballet foot" deformity.

(2) Electrocardiogram (ECG) Examination: The ECG is normal in most patients. Some patients exhibit biphasic or inverted T waves in leads II, III, and aVF, along with nonspecific ST-segment changes, which become more pronounced after amyl nitrite inhalation or exercise. The ST-T wave changes may be related to papillary muscle ischemia, increased left ventricular tension due to valve prolapse, or sympathetic hyperactivity. Prolongation of the QT interval may be observed. Various arrhythmias are common, including atrial premature beats, ventricular premature beats, supraventricular or ventricular tachycardia, sinus node dysfunction, and varying degrees of atrioventricular block. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome may also be seen.

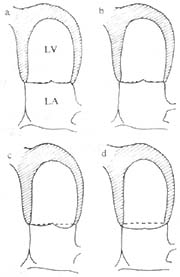

(3) Echocardiography: This is particularly significant for diagnosing mitral valve prolapse. Two-dimensional echocardiography in the parasternal long-axis view shows the mitral valve leaflets bulging into the left atrium during systole, exceeding the annular level. Additionally, the mitral valve may exhibit significant ballooning, thickened and redundant leaflets, annular dilatation, left atrial and ventricular enlargement, and elongated or ruptured chordae tendineae. M-mode echocardiography reveals systolic bowing of the mitral valve closure line (CD segment) posteriorly by more than 2 mm and holosystolic posterior displacement exceeding 3 mm (Figure 1). Furthermore, a segment of the leaflet or both leaflets may show a hammock-like appearance during systole.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of two-dimensional echocardiography in the apical four-chamber view.

a. Grade I prolapse of the posterior mitral leaflet beyond the annulus;

b. Grade I prolapse of the anterior mitral leaflet beyond the annulus;

a and b. The coaptation point of the valve leaflets is within the left ventricle;

c. Grade II prolapse of both anterior and posterior mitral leaflets beyond the annulus, with the coaptation point at the annular level;

d. Grade III prolapse of both anterior and posterior mitral leaflets beyond the annulus, with the coaptation point also beyond the annulus.

(LA: left atrium, LV: left ventricle)

Clinical diagnosis is primarily based on typical mid-systolic clicks and late systolic blowing murmurs at the cardiac apex, the influence of drugs and maneuvers on the murmurs, and electrocardiographic findings which have auxiliary diagnostic value. Echocardiography can provide a definitive diagnosis.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic individuals do not require treatment and can maintain normal work and life, with regular follow-ups. Those with a history of syncope, a family history of sudden death, complex ventricular arrhythmias, or Marfan syndrome should avoid excessive physical labor and strenuous exercise.

For those experiencing chest pain, beta-blockers can be used to reduce myocardial oxygen consumption and ventricular wall tension, slow heart rate, weaken myocardial contractility, and improve the degree of mitral valve prolapse, thereby alleviating chest pain. Nitrates may worsen mitral valve prolapse and should be used with caution.

For those with mitral regurgitation, prophylactic antibiotics should be administered before and after surgery, tooth extraction, childbirth, or invasive examinations to prevent infective endocarditis.

For arrhythmias accompanied by palpitations, dizziness, vertigo, or a history of syncope, beta-blockers can be used. If ineffective, phenytoin sodium, quinidine, etc., may be considered, and combination therapy may be necessary in some cases.

For transient ischemic attacks, antiplatelet agents such as aspirin should be used. If ineffective, anticoagulants may be considered to prevent cerebral embolism.

Severe mitral regurgitation with congestive heart failure often requires surgical intervention. For cases with elongated or ruptured chordae, annular dilation, or thickened but mobile mitral valves without calcification, valve repair is preferred. For those unsuitable for valve repair, prosthetic valve replacement is recommended.

(1) Congestive Heart Failure Severe mitral regurgitation leads to progressive congestive heart failure, caused by the gradual enlargement of the valve annulus and elongation of the chordae tendineae, which worsens mitral regurgitation over time. It can also occur acutely, often due to chordae tendineae rupture or concurrent infective endocarditis.

(2) Infective Endocarditis More common in males and individuals over 45 years old, with an incidence rate of 1–10%. If an isolated click develops into a systolic murmur or the murmur duration prolongs, accompanied by unexplained fever, infective endocarditis should be considered.

(3) Arrhythmias and Sudden Death Patients with mitral valve prolapse are prone to arrhythmias, which generally do not affect health. Ventricular arrhythmias are the most common, occurring in over 50% of cases. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is also relatively common. The mechanism remains unclear but may be related to traction on the mitral valve leaflets, papillary muscles, or chordae tendineae, or increased sympathetic activity.

Sudden death may rarely occur, with higher risk under the following conditions: severe mitral valve prolapse with left ventricular decompensation; complex ventricular arrhythmias; significantly prolonged QT interval; positive ventricular late potentials; atrial flutter or fibrillation with pre-excitation syndrome; young females with a history of amaurosis, syncope, and dyspnea.

(4) Transient Ischemic Attacks and Embolism Mostly caused by cerebral embolism, with an incidence rate of up to 40% in mitral valve prolapse patients under 45. Studies suggest that mitral valve prolapse patients often exhibit increased platelet activity. Additionally, fibrosis of the left ventricular endocardium due to friction between the mitral valve's atrial surface, chordae tendineae, and the left ventricular wall predisposes to thrombus formation. Thrombus detachment can lead to cerebral embolism, retinal artery embolism, and systemic embolisms (coronary artery, renal artery, splenic artery, mesenteric artery, etc.). Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation is often a precursor to cerebral embolism.