| disease | Rectovaginal Fistula |

| alias | Rectovaginal Fistual |

A rectovaginal fistula is a connection between the rectum and the vagina. If the fistula is large and allows unobstructed passage of feces, it may be asymptomatic. Most rectovaginal fistulas occur in congenital anorectal malformations.

bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of rectovaginal fistula range from grade I fecal leakage to significant fecal leakage. When the fistula is small or there is anal stenosis or anal atresia, it presents as chronic incomplete intestinal obstruction. Within days after birth, or even months or after 2-3 years of age, the child may experience difficulty in defecation, with persistent constipation that sometimes requires enemas or laxatives to relieve. If the fistula is large, there are no obstructive symptoms, but symptoms such as abnormal defecation position, painful defecation, and stool deformation may occur.

The diagnosis of rectovaginal fistula can generally be made based on clinical manifestations and pre-existing disease symptoms, but the exact location of the fistula must be accurately determined to guide treatment. To locate the fistula, a probe can be inserted to trace its path, or a rectal examination can be performed. If necessary, a fistulography should be conducted to confirm the fistula's position. Another method involves placing gauze in the vagina and injecting methylene blue into the rectum. After a few minutes, the gauze is removed to check for blue staining, which confirms the presence of a vaginal fistula.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

All types of congenital anorectal malformations require surgical treatment. However, the timing and method of surgery may vary depending on the type of malformation and the size of the fistula. The goal of surgery is to restore normal bowel control function. Due to the complex causes, diverse types, high postoperative infection and recurrence rates, and significant surgical difficulty associated with rectovaginal fistula, the choice of surgical procedure is extremely important to achieve success in one attempt.

For congenital anal malformations and rectovaginal fistula, the following should be noted: ① the surgical method and technique; ② whether the distal rectum is sufficiently mobilized; ③ avoiding severe infection; ④ fully releasing the rectal mucosal end to achieve tension-free suturing.Imperforate anus with low rectovaginal fistula (fossa navicularis fistula): For cases with a very small fistula and difficulty in defecation since birth, a stoma can be created during the neonatal period. If the fistula is very close to the vaginal opening, anoplasty can be performed after 4–5 years of age. If the vaginal fistula is large and stool passes smoothly, early surgery is unnecessary, and surgery at 3–5 years of age is more appropriate.

For acquired rectovaginal fistula, especially iatrogenic rectovaginal fistula, the timing of surgery should be carefully selected. Do not rush into surgery due to the patient's urgent demands. Surgery should be delayed until all inflammation has subsided and scars have softened, typically 3 months after the injury or prior repair. If the fistula is large, wait 6 months. Additionally, all inflammation must be properly drained.

Surgical Methods

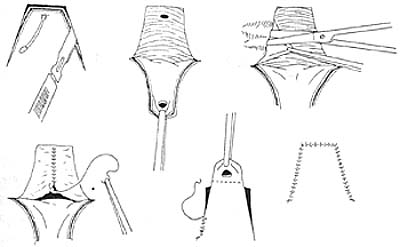

(1) Fistulectomy with layered suturing (Figure 1)

Figure 1 Fistulectomy with layered suturing

After excising the fistula, layered suturing is performed, which can be repaired via the vagina or rectum. The advantage is that the procedure is simple and easy to perform. The disadvantage is the high recurrence rate due to tension during suturing and uneven separation of rectal or vaginal tissue. Therefore, the mucosal-muscular flap must have adequate blood supply.

1. Surgical Method: The posterior and lateral aspects of the rectal blind end are mobilized, followed by separation around the rectovaginal fistula. After mobilizing and ligating the fistula, the rectovaginal septum is sutured intermittently with fine catgut. Then, the rectum is fully mobilized to allow tension-free suturing with the distal mucosal muscle layer. Postoperatively, keep the wound clean and dry for initial healing. Anal dilation should begin 2 weeks postoperatively and continue for no less than 6 months to prevent anal stricture. This procedure is suitable for low imperforate anus, low rectovaginal fistula, or rectovestibular fistula. The success rate increases with the patient's age.

2. Outcomes: Reported outcomes vary. Lescher et al. reported a postoperative recurrence rate of 84%, while Given reported 30%. Hibband reported initial healing in 14 cases. Although some do not recommend this surgery for high rectovaginal fistula, Lawson reported success in 42 out of 53 cases of high rectovaginal fistula and suggested incising the rectouterine pouch to facilitate fistula suturing. The key points of this procedure are tension-free suturing and ensuring no ischemia at the sutured site.(2) Rectal advancement flap repair (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Rectal advancement flap repair

In 1902, Noble first used the rectal advancement flap repair to treat rectovaginal fistula. Recently, most scholars consider this method the first choice for repairing low rectal fistula.

After satisfactory anesthesia, the patient was placed in the prone position. First, the internal and external openings were identified, and a probe was inserted into the fistula tract. A "U"-shaped incision was made for the rectal mucosal flap, ensuring the length-to-width ratio did not exceed 2:1 and maintaining adequate blood supply. A 1:20,000 adrenaline solution was injected submucosally to reduce bleeding. The internal sphincter was dissected and sutured at the midline. A 0.3 cm wide strip of mucosal tissue around the fistula opening was excised to create a wound surface. The mobilized flap was then pulled down to cover the internal opening wound and intermittently sutured with 2-0 or 3-0 gut sutures, restoring the normal anatomical relationship between the mucosa and skin. The vaginal wound was left unsutured for drainage purposes.

(3) Sacroabdominoperineal Surgery

Since the levator ani muscle in newborns is only about 1.5 cm away from the anus, it is extremely easy to injure the puborectalis ring when dissecting the rectum in the perineal region. The sacrococcygeal incision allows clear identification of the puborectalis ring, facilitates the mobilization of the rectum, and makes it easier to separate and excise higher fistulas. This procedure is suitable for infants older than 6 months. A longitudinal skin incision of about 3–5 cm is made in the sacrococcygeal region, and the sacrococcygeal cartilage is transversely incised to expose the rectal blind end. A longitudinal incision is made along the rectal blind end to locate the fistula in the intestinal lumen, which is then separated and cut before being sutured. The rectum is mobilized until it can relax and descend to the level of the anal skin. An X-shaped incision is made in the anal skin to expose the external sphincter, and the rectum is slowly pulled through the puborectalis ring to the anus, ensuring the intestinal segment is not twisted and avoiding forceful digital dilation within the intestinal ring. The rectal wall is sutured to the subcutaneous tissue of the anus with silk threads, and the full thickness of the rectum is intermittently sutured to the anal skin using 3-0 catgut or silk threads. The sacrococcygeal wound is closed sequentially.

Additionally, high rectal atresia and rectovaginal fistulas can also be treated with abdominoperineal anoplasty, rectovaginal fistula repair, and colostomy during the neonatal period. However, due to practical limitations and high surgical mortality rates, this approach is often difficult for parents to accept.The main surgical complications for all high fistulas are infection and fistula recurrence, and reoperation is considerably more challenging. A treatment plan should be tailored to each specific case based on the condition and practical circumstances, selecting the most appropriate surgical method.

For acquired rectovaginal fistulas, treatment should be determined by the disease cause. If caused by inflammation, active treatment of enteritis should be followed by selecting repair, intestinal resection, or colostomy based on the condition.

For rectovaginal fistulas caused by obstetric surgery or trauma, transrectal or vaginal repair should be performed after inflammation is controlled. The edges of the rectal and vaginal walls are incised and separated, and the rectal wall is closed with transverse invagination. The submucosal tissue of the vaginal wall is longitudinally aligned, and the vaginal mucosa is closed transversely.

Local repair of radiation-induced rectovaginal fistulas is extremely difficult and often impossible, so colostomy should be performed.

For rectovaginal fistulas caused by foreign bodies or electrocautery, an initial-stage [first-stage] colostomy should be performed first, followed by an intermediate-stage [second-stage] fistula repair and intestinal anastomosis or pull-through procedure.

Currently, there are many surgical methods for rectovaginal fistulas, but the optimal approach should be selected for each specific case to minimize injury and achieve the best outcome.