| disease | Rectocele |

| alias | RC, Rectocele |

Rectocele (RC) is translated as rectal protrusion, which refers to the bulging of the anterior rectal wall, also known as anterior rectal protrusion. It is one of the outlet obstruction syndromes. The weakening of the rectovaginal septum causes the rectal wall to protrude into the vagina, which is also one of the main factors contributing to defecation difficulties. This condition is more common in middle-aged and elderly women, but cases in men have also been reported in recent years.

bubble_chart Etiology

The anterior wall of the rectum is supported by the rectovaginal septum, which is primarily composed of the pelvic fascia, including the midline intersecting fibrous tissue of the levator ani muscle and the perineal body. If the rectovaginal septum becomes lax, the anterior rectal wall is prone to protrude forward, resembling a hernia. This condition is commonly seen in women with chronic constipation leading to prolonged increases in intra-abdominal pressure, multiparous women, individuals with poor bowel habits, and elderly women with perineal laxity.

Domestic studies involving 45 patients with rectocele conducted routine examinations, anorectal dynamics, pelvic floor electromyography, defecography, and anorectal motility tests. These studies proposed the following insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of rectocele, defining it as a pathological state where the anterior rectal wall excessively protrudes into the vagina during defecation. During normal defecation, intra-abdominal pressure rises, the pelvic floor muscles relax, the anorectal angle becomes obtuse, the pelvic floor forms a funnel shape, and the anal canal becomes the lowest point, allowing feces to be expelled under defecatory pressure. Due to the influence of the sacral curve, the vertical component of descending fecal matter becomes the driving force for defecation, while the horizontal component acts on the anterior rectal wall, causing it to protrude forward. In males, the anterior region is more robust, making rectal protrusion less likely. In females, however, the anterior region is more vulnerable, and this horizontal force acts on the rectovaginal septum. The rectovaginal septum contains the puboperineal fascia and the intersecting fibers of the levator ani muscle, both of which significantly strengthen the septum to resist this horizontal force, preventing excessive protrusion of the anterior rectal wall during defecation and maintaining the direction of fecal movement.

Childbirth, developmental abnormalities, fascial degeneration, and prolonged increases in intra-abdominal pressure can all damage and relax the pelvic floor. Particularly during childbirth, the intersecting fibers within the levator ani muscle may tear, and the puboperineal fascia may become overstretched or torn, thereby weakening the rectovaginal septum and impairing its ability to resist the horizontal defecatory force, leading to gradual anterior protrusion. Most patients in this group developed the condition postpartum, suggesting a link to vaginal delivery. The prevalence in middle-aged individuals also hints at a possible association with connective tissue degeneration.Once protrusion occurs, its apex breaches the pelvic diaphragm, becoming the lowest point during defecation, with its longitudinal axis aligned with the direction of fecal descent. Fecal matter descending along the sacral curve first enters the protrusion. If the stool is dry and hard or the pelvic floor fails to relax synchronously, defecatory pressure will primarily act on the apex of the protrusion. Patients may feel perineal fullness, but feces remain difficult to expel. As the direction of defecatory pressure shifts and is partially dissipated, pressure on the posterior rectal wall decreases. The defecation receptors, mainly located in this area, are inadequately stimulated, preventing full relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles and opening of the anal canal's upper orifice, making it hard to guide feces into the anal canal. The sensation of perineal fullness compels patients to strain further, creating a vicious cycle that deepens the protrusion and further descends the pelvic floor. Patients with pelvic floor spasm syndrome experience paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during difficult defecation, actively protecting the anterior rectal wall and pelvic floor. Consequently, these patients exhibit less pelvic floor descent and shallower rectoceles. This suggests a close relationship between rectocele and pelvic floor laxity, with pelvic floor damage likely being the initiating factor. The resulting rectocele, in turn, exacerbates pelvic floor descent, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle.

When the pelvic floor descends, the pudendal nerve that innervates the pelvic floor muscles is inevitably stretched. The terminal portion of this nerve is approximately 90 mm long and should not be stretched beyond 12%. In this group of patients, the nerve was stretched by 19.4% at rest and 31.3% during defecation. Such repeated excessive stretching can lead to functional or structural damage to the nerve, causing the levator ani and external sphincter muscles it innervates to gradually weaken, manifesting as a decrease in contraction pressure. Read suggested that pudendal nerve injury can reduce rectal sensory function, decrease rectal wall tension, and dull the rectal contraction reflex. Literature confirms that the rectal attachment of the levator ani muscle and the puborectalis muscle both contain abundant visceral nerve fibers. Therefore, the sensation of defecation and reflexive rectal contractions may also be related to this. Abnormal descent of the pelvic floor is also likely to cause injury to these visceral nerves. Among the 54 patients, anal canal contraction pressure, defecation sensation capacity, rectal contraction waves, and contraction rate were all decreased, indicating pelvic floor nerve injury. Nerve damage can exacerbate pelvic floor dysfunction, further impairing non-defecation functions, creating a vicious cycle of mutual causation.The pelvic floor neuromuscular injury causes abnormal descent, and the supported tissues and organs also relax and descend, leading to various pathological changes. Examination results indicate that rectocele is almost always combined with other types of relaxation-related sexually transmitted diseases, suggesting that rectocele is part of a complex pathological process.

In summary, the author believes that rectocele is not an independent pathological change but may be a manifestation of pelvic floor relaxation syndrome.bubble_chart Clinical Manifestations

Difficulty in defecation is the main symptom of rectocele. When straining to defecate, increased abdominal pressure forces the stool into the protruding area, and when the straining stops, the stool is pushed back into the rectum, causing difficulty in defecation. As stool accumulates in the rectum, the patient feels a sensation of heaviness and incomplete evacuation, leading to further straining. This further increases abdominal pressure, placing greater stress on the already weakened rectovaginal septum and deepening the rectocele. This creates a vicious cycle, progressively worsening the difficulty in defecation. A few patients may need to apply pressure around the anus or inside the vagina to assist with defecation, or even insert fingers into the rectum to manually remove stool. Some patients experience hematochezia and anal pain.

bubble_chart Auxiliary Examination

Digital rectal examination and defecography are the main diagnostic methods for rectocele.

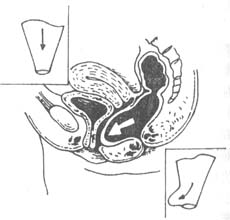

(1) Digital examination: During a digital rectal exam, a circular or oval weak area can be palpated on the anterior rectal wall at the upper end of the anal canal, protruding toward the vagina. The protrusion becomes more pronounced during straining (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Rectocele

(2) Defecography: This reveals forward protrusion of the anterior rectal wall and difficulty in barium passage through the anal canal. The protrusion often appears as a pouch, goose-head angle, or mound with smooth edges. If the depth of the protrusion exceeds 2 cm, barium retention is commonly observed within the pouch. In cases involving puborectalis muscle abnormalities, a "goose sign" is often present.

(3) Balloon expulsion test: A catheter with an attached balloon is inserted into the rectal ampulla, and 100 ml of air is injected. The patient is instructed to strain as if defecating to assess rectal evacuation function. Normally, the balloon is expelled within 5 minutes; delayed expulsion is defined as exceeding 5 minutes. Among 39 cases examined by the author, 2 cases showed normal expulsion, while 16 cases took >5 minutes, 8 cases >7 minutes, 5 cases >10 minutes, 6 cases around 15 minutes, and 2 cases failed to expel the balloon even after >15 minutes, yielding a positive rate of 94.9%.

Based on the typical medical history, symptoms, and signs, the diagnosis of rectocele is not difficult. In normal individuals, during forceful defecation, a forward bulge can sometimes be observed above the anterior aspect of the anorectal junction, which is relatively long but generally does not exceed 5 cm in depth. The domestic medical community has proposed a defecography grading system for rectocele, dividing it into grade III: grade I, with a protrusion depth of 0.6–1.5 cm; grade II, 1.6–3 cm; and grade III, ≥3.1 cm.

Additionally, Nichols et al. suggested classifying rectocele into three types: low, middle, and high. Low rectocele is often caused by perineal tearing during childbirth; middle rectocele is the most common and is typically due to birth trauma; high rectocele results from damage or pathological relaxation of the upper third of the vagina, cardinal ligaments, or uterosacral ligaments, often accompanied by posterior vaginal hernia, vaginal eversion, and uterine prolapse.

bubble_chart Treatment Measures

Conservative treatment is initially adopted, but the use of harsh laxatives and enemas is not advocated. Instead, emphasis is placed on the "three more": consuming more coarse staple foods or fruits and vegetables rich in dietary fiber; drinking more water, with a daily total of 2000–3000 ml; and engaging in more physical activity. Through the above treatments, most patients experience varying degrees of symptom improvement. For those whose symptoms show no improvement or insignificant efficacy after three months of regular non-surgical treatment, surgical intervention may be considered. The surgical methods mainly fall into the following three categories:

(1) Transrectal Repair: The patient is placed in a prone position with the lower limbs hanging at approximately 45º, and the lower abdomen and pubic symphysis are slightly elevated. Spinal or sacral anesthesia may be used. Wide adhesive tape is applied to both buttocks and pulled laterally to expose the anal area. The buttocks, anus, and vagina are routinely disinfected, and the anus is gently dilated with fingers to accommodate 4–6 fingers. A right-angle retractor or S-shaped retractor is inserted into the anus, and an assistant helps expose the anterior rectal wall. The specific surgical methods are divided into two types.

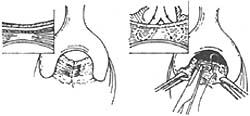

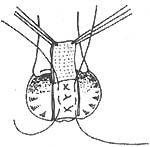

1. **Sehapayah Method (Figure 1)**: A longitudinal incision is made 0.5 cm above the dentate line in the lower rectum, approximately 7 cm long and deep enough to reach the submucosal layer, exposing the muscle layer. Depending on the width of the rectocele, the bilateral mucosal flaps are freed by 1–2 cm. The left index finger is inserted into the vagina to lift the posterior vaginal wall toward the rectum, facilitating hemostasis and preventing vaginal injury. Then, 2/0 chromic catgut sutures are used, with the needle entry point determined by the degree of rectocele, usually at the edge of the normal tissue of the rectocele. The needle may enter from the right levator ani muscle edge outward to inward, then exit from the left levator ani muscle edge, allowing the right index finger to palpate a vertical and sturdy muscle column. During suturing, the needle tip must not penetrate the vaginal posterior wall mucosa to avoid rectovaginal fistula. Finally, the bilateral mucosal flaps are trimmed, and the mucosal incision is closed with interrupted chromic catgut sutures. A Vaseline gauze strip is placed in the rectum and brought out through the anus.

**Figure 1: Rectocele Repair Method (Sehapayah Method)**

Left: Longitudinal incision made above the dentate line

Right: Interrupted sutures to repair the depressed area

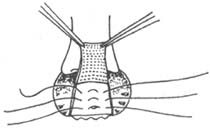

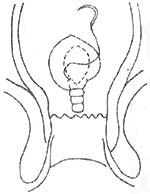

2. **Khubchandani Method (Figure 2)**: A transverse incision is made at the dentate line, 1.5–2 cm long, with vertical incisions extending upward at both ends, each about 7 cm long, forming a "U" shape. A broad-based mucosal-muscular flap (which must include the muscle layer) is freed, and the mucosal-muscular flap is dissected upward beyond the weakened area of the rectovaginal septum. First, 3–4 interrupted horizontal sutures are placed to fold the松弛的直肠阴道隔; then, 2–3 interrupted vertical sutures are added to shorten the anterior rectal wall, reduce tension on the sutured mucosal-muscular flap, and promote healing. Excess mucosa is excised, and the edges of the mucosal-muscular flap are sutured to the dentate line with interrupted sutures. Finally, the bilateral longitudinal incisions are closed with interrupted or continuous sutures.

(1) Mucosal-muscular flap incision made above the dentate line

(2)松弛的直肠阴道隔 folded with 3 or 4 horizontal sutures

(3) Vertical sutures added after horizontal folding for reinforcement

**Figure 2: Transrectal Repair Method for Rectocele (Khubchandani Method)**

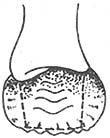

(2) Transrectal closed repair (Block method) (Figure 3): According to the size of the rectocele, use curved hemostatic forceps to longitudinally clamp the rectal mucosa layer, then continuously suture the mucosal muscle layer from bottom to top with 2/0 chromic catgut until reaching the pubic symphysis. The suturing should be wider at the bottom and narrower at the top to avoid forming a mucosal flap at the upper end that could affect defecation. This method is only suitable for smaller rectoceles (1-2 cm).

Figure 3 Closed repair of rectocele using the tonifying method

Advantages of the transrectal approach for rectocele repair: ① The method is simple and convenient; it can simultaneously treat other accompanying anorectal diseases; ② The surgery can be performed under local anesthesia; ③ It provides more direct access to the suprasphincteric region, allowing anterior plication of the puborectalis muscle and reconstruction of the anorectal angle. The disadvantage is that it cannot correct bladder protrusion or posterior vaginal hernia, and it is also not suitable for transanal repair in cases with anal stenosis. For patients with these conditions, vaginal repair is preferable.

(3) Closed rectocele repair with internal rectal suturing: The key surgical steps involve performing double continuous interlocking sutures at the rectocele site, stitching together the rectal mucosa, submucosal tissue, and muscle layer to eliminate the anterior rectal wall pouch. The continuous interlocking sutures should be tightened to achieve a strangulation effect, causing mucosal necrosis and sloughing, while relying on the submucosal and muscle layer tissues for rapid wound healing. This procedure is suitable for mid-level rectoceles and is characterized by its speed, simplicity, and minimal bleeding. However, it may sometimes result in incomplete closure of the rectocele, leading to postoperative recurrence.

It is important to note that isolated rectoceles are rare, and most cases are accompanied by conditions such as anterior rectal mucosal prolapse, internal rectal intussusception, perineal descent, or enterocele. Concurrent treatment of these associated conditions is necessary during surgery; otherwise, the therapeutic outcome may be compromised. Additionally, thorough preoperative preparation and postoperative care are essential. Preoperative measures include oral administration of intestinal antibiotics for 3 days, a soft diet for 2 days, fasting on the day of surgery, and bowel preparation with enemas and vaginal irrigation. Postoperatively, antibiotics or metronidazole should be continued to prevent infection, and a liquid diet should be maintained to avoid bowel movements for 5–7 days.